John Denver

John Denver | |

|---|---|

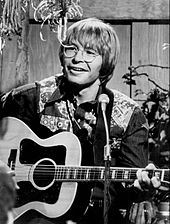

Denver in 1974 | |

| Born | Henry John Deutschendorf Jr. December 31, 1943 Roswell, New Mexico, U.S. |

| Died | October 12, 1997 (aged 53) Monterey Bay near Pacific Grove, California, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Blunt force trauma as a result of a plane crash |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1962–1997 |

| Spouses |

|

| Children | 3[a] |

| Musical career | |

| Genres | |

| Instruments |

|

| Labels | |

| Formerly of |

|

| Website | johndenver |

Henry John Deutschendorf Jr. (December 31, 1943 – October 12, 1997),[3] known professionally as John Denver, was an American singer, songwriter, and actor. He was one of the most popular acoustic artists of the 1970s and one of the best selling artists in that decade.[4] AllMusic has called Denver "among the most beloved entertainers of his era".[5]

Denver recorded and released approximately 300 songs, about 200 of which he wrote himself. He had 33 albums and singles that were certified Gold and Platinum in the U.S by the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA),[6] with estimated sales of more than 33 million units.[7] He recorded and performed primarily with an acoustic guitar and sang about his joy in nature, disdain for city life, enthusiasm for music, and relationship trials. Denver's music appeared on a variety of charts, including country music, the Billboard Hot 100, and adult contemporary, earning 12 gold and four platinum albums with his signature songs "Take Me Home, Country Roads"; "Poems, Prayers & Promises"; "Annie's Song"; "Rocky Mountain High"; "Calypso"; "Thank God I'm a Country Boy"; and "Sunshine on My Shoulders".

Denver appeared in several films and television specials during the 1970s and 1980s, including the 1977 hit Oh, God!, in which he starred alongside George Burns. He continued to record into the 1990s, also focusing on environmental issues as well as lending vocal support to space exploration and testifying in front of Congress to protest censorship in music.[8] Known for his love of Colorado, Denver lived in Aspen for much of his life. In 1974, Denver was named poet laureate of the state. The Colorado state legislature also adopted "Rocky Mountain High" as one of its two state songs in 2007, and West Virginia did the same for "Take Me Home, Country Roads" in 2014. An avid pilot, Denver was killed at age 53 in a single-fatality crash while piloting a recently purchased light plane in 1997.

Early life

[edit]Henry John Deutschendorf Jr. was born on December 31, 1943, in Roswell, New Mexico, to Erma Louise (née Swope; 1922–2010) and Captain Henry John "Dutch" Deutschendorf Sr. (1920–1982),[9] a United States Army Air Forces pilot stationed at Roswell Army Air Field. Captain Deutschendorf Sr. was a decorated pilot who set a number of air speed records in a Convair B-58 Hustler in 1961.[10]

In his 1994 autobiography Take Me Home, Denver described his father as a stern man who could not show his love for his children. With a military father, Denver's family moved often, and he found difficulty gaining friends and assimilating with children of his own age. The introverted Denver often felt misplaced and did not know where he truly belonged.[12] While stationed at Davis–Monthan Air Force Base in Tucson, Arizona, the Deutschendorfs purchased a house and lived there from 1951 to 1959.[13] Denver lived in Tucson from ages six to 14.[14]

During these years, Denver attended Mansfeld Junior High School[15] and was a member of the Tucson Arizona Boys Chorus for two years. He was content in Tucson, but his father was transferred to Maxwell Air Force Base in Montgomery, Alabama. The family later moved to Carswell Air Force Base in Fort Worth, Texas, where Denver graduated from Arlington Heights High School. Denver was distressed with life in Fort Worth, and in his third year of high school, he drove his father's car to California to visit family friends and begin his music career. His father flew to California in a friend's jet to retrieve him, and Denver reluctantly returned to complete his schooling.[16]

Career

[edit]Early career

[edit]At age 11, Denver received an acoustic guitar from his grandmother.[17] He learned to play well enough to perform at local clubs by the time he was in college. Denver decided to change his name when Randy Sparks, founder of the New Christy Minstrels, suggested that "Deutschendorf" would not fit comfortably on a marquee.[18] Denver attended Texas Tech University in Lubbock and sang in a folk-music group, "The Alpine Trio", while studying architecture.[19][20][21] He was also a member of the Delta Tau Delta fraternity. Denver dropped out of Texas Tech in 1963[17] and moved to Los Angeles, where he sang in folk clubs. In 1965, Denver joined The Chad Mitchell Trio, replacing founder Chad Mitchell. After more personnel changes, the trio later became known as "Denver, Boise, and Johnson" (John Denver, David Boise, and Michael Johnson).[17]

In 1969, Denver abandoned band life to pursue a solo career and released his first album for RCA Records, Rhymes & Reasons. Two years earlier, he had made a self-produced demo recording of some of the songs he played at his concerts. It included a song Denver had written called "Babe, I Hate to Go", later renamed "Leaving on a Jet Plane". He made several copies and gave them out as presents for Christmas.[22] Milt Okun, who produced records for The Chad Mitchell Trio and folk group Peter, Paul and Mary, had become Denver's producer as well. Okun brought the unreleased "Jet Plane" song to Peter, Paul and Mary. Their rendition hit number one on the Billboard Hot 100.[23] Denver's song also made it to No. 2 in the UK in February 1970, having also made No. 1 on the US Cash Box chart in December 1969.

RCA did not actively promote Rhymes & Reasons with a tour, but Denver embarked on an impromptu supporting tour throughout the Midwest, stopping at towns and cities, offering to play free concerts at local venues. When he was successful in persuading a school, college, American Legion hall, or coffeehouse to let him play, Denver distributed posters in the town and usually showed up at the local radio station, guitar in hand, offering himself for an interview.[24] As the writer of "Leaving on a Jet Plane", Denver was often successful in gaining some promotional airtime, usually performing one or two songs live. Some venues let him play for the 'door'; others restricted him to selling copies of the album at intermission and after the show. After several months of this, Denver had built a solid fan base, many of whom remained loyal throughout his career.[17]

Denver recorded two more albums in 1970, Take Me to Tomorrow and Whose Garden Was This, including a mix of songs he had written and covers.

Career peak

[edit]

Denver's next album, Poems, Prayers & Promises (1971), was a breakthrough for him in the United States, thanks in part to the single "Take Me Home, Country Roads", which went to No. 2 on the Billboard charts despite the first pressings of the track being distorted. Its success was due in part to the efforts of his new manager, future Hollywood producer Jerry Weintraub, who signed Denver in 1970. Weintraub insisted on a reissue of the track and began a radio airplay campaign that started in Denver, Colorado. Denver's career flourished thereafter, and he had a series of hits over the next four years. In 1972, Denver had his first Top Ten album with Rocky Mountain High, with its title track reaching the Top Ten in 1973.[25] In 1974 and 1975, Denver had a string of four No. 1 songs ("Sunshine on My Shoulders", "Annie's Song", "Thank God I'm a Country Boy", and "I'm Sorry") and three No. 1 albums (John Denver's Greatest Hits, Back Home Again, and Windsong).[26]

In the 1970s, Denver's onstage appearance included long blond hair and wire-rimmed "granny" glasses. His embroidered shirts with images commonly associated with the American West were created by the designer and appliqué artist Anna Zapp. Weintraub insisted on a significant number of television appearances, including a series of half-hour shows in the United Kingdom, despite Denver's protests at the time, "I've had no success in Britain ... I mean none".[27] In December 1976, Weintraub told Maureen Orth of Newsweek: "I knew the critics would never go for John. I had to get him to the people."

After appearing as a guest on many shows, Denver hosted his own variety and music specials, including several concerts from Red Rocks Amphitheatre. His seasonal special, Rocky Mountain Christmas, was watched by more than 60 million people and was the highest-rated show for the ABC network at that time.

In 1973, Denver starred in his own BBC television series, The John Denver Show, a weekly music and variety show directed and produced by Stanley Dorfman.

Denver's live concert special, An Evening with John Denver, won the 1974–1975 Emmy Award for Outstanding Special, Comedy-Variety or Music.[28] When Denver ended his business relationship in 1982 because of Weintraub's focus on other projects,[29] Weintraub threw Denver out of his office and accused him of Nazism. Denver later told Arthur Tobier, when the latter transcribed his autobiography,[14] "I'd bend my principles to support something he wanted of me. And of course, every time you bend your principles — whether because you don't want to worry about it, or because you're afraid to stand up for fear of what you might lose — you sell your soul to the devil".[30]

Denver was also a guest star on The Muppet Show, the beginning of the lifelong friendship between Denver and Jim Henson that spawned two television specials with the Muppets, A Christmas Together and Rocky Mountain Holiday. He also tried acting, appearing in "The Camerons are a Special Clan" episode of the Owen Marshall, Counselor at Law television series in October 1973 and "The Colorado Cattle Caper" episode of the McCloud television series in February 1974. In 1977, Denver starred in the hit comedy film Oh, God! opposite George Burns. He also hosted the Grammy Awards five times in the 1970s and 1980s, and guest-hosted The Tonight Show on several occasions. In 1975, Denver was awarded the Country Music Association's Entertainer of the Year award. At the ceremony, the outgoing Entertainer of the Year, Charlie Rich, presented the award to his successor after he set fire to the slip of paper containing the official notification of the award.[31][32] Some speculated Rich was protesting the selection of a non-traditional country artist for the award, but Rich's son disputes that, saying his father was drunk, taking pain medication for a broken foot, and just trying to be funny. Denver's music was defended by country singer Kathy Mattea, who told Alanna Nash of Entertainment Weekly: "A lot of people write him off as lightweight, but he articulated a kind of optimism, and he brought acoustic music to the forefront, bridging folk, pop, and country in a fresh way ... People forget how huge he was worldwide."

In 1977, Denver co-founded The Hunger Project with Werner Erhard and Robert W. Fuller. He served for many years and supported the organization until his death. President Jimmy Carter appointed Denver to serve on the President's Commission on World Hunger. Denver wrote the song "I Want to Live" as the commission's theme song. In 1979, Denver performed "Rhymes & Reasons" at the Music for UNICEF Concert. Royalties from the concert performances were donated to UNICEF.[33]

Denver's father taught him to fly in the mid-1970s, which led to their reconciliation.[19] In 1980, Denver and his father, by then a lieutenant colonel, co-hosted an award-winning television special, The Higher We Fly: The History of Flight.[34] It won the Osborn Award from the Aviation/Space Writers' Association, and was honored by the Houston Film Festival.[34]

Political views and activism

[edit]In the mid-1970s, Denver became outspoken in politics. He expressed his ecologic interests in the epic 1975 song "Calypso", an ode to the eponymous exploration ship RV Calypso used by Jacques Cousteau. In 1976, Denver campaigned for Jimmy Carter, who became a close friend and ally. Denver was a supporter of the Democratic Party and of a number of charitable causes for the environmental movement, the homeless, the poor, the hungry, and the African AIDS crisis. He founded the charitable Windstar Foundation in 1976 to promote sustainable living. Denver's dismay at the Chernobyl disaster led to precedent-setting concerts in parts of communist Asia and Europe.[19]

During the 1980s, Denver was critical of Ronald Reagan’s administration and remained active in his campaign against hunger, for which Reagan awarded Denver the Presidential World Without Hunger Award in 1987.[19] Denver's criticism of the conservative politics of the 1980s was expressed in his autobiographical folk-rock ballad "Let Us Begin (What Are We Making Weapons For?)". In an open letter to the media, Denver wrote that he opposed oil drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. He had battled to expand the refuge in the 1980s, and he praised President Bill Clinton for his opposition to the proposed drilling. The letter, which Denver wrote in the midst of the 1996 United States presidential election, was one of the last he ever wrote.[19] In 1992, Denver, along with fellow singers Liza Minnelli and John Oates, performed a benefit to fight the passage of Amendment 2, an anti-LGBT ballot measure that prevented Colorado municipalities from enacting anti-discrimination protections.[35] Denver was also on the National Space Society's board of governors for many years.

Later years and humanitarian efforts

[edit]Denver had a few more US Top 30 hits as the 1970s ended, but nothing to match his earlier success. Denver began to focus more on humanitarian and sustainability causes, focusing extensively on nature conservation projects. He made public expression of his acquaintances and friendships with ecological design researchers such as Richard Buckminster Fuller (about whom he wrote and composed "What One Man Can Do") and Amory Lovins, from whom he said he learned much. Denver also founded the environmental group Plant-It 2020 (originally Plant-It 2000). He also had a keen interest in solutions to world hunger and visited Africa during the 1980s to witness firsthand the suffering caused by starvation and work with African leaders toward solutions.

From 1973 to at least 1979, Denver annually performed at the fundraising picnic for the Aspen Camp School for the Deaf, raising half of the camp's annual operating budget.[36] During the Aspen Valley Hospital's $1.7 million capital campaign in 1979, Denver was the largest single donor.[36]

In 1983 and 1984, Denver hosted the annual Grammy Awards, which he had previously done in 1977, 1978, and 1979. In the 1983 finale, he was joined on stage by folk music legend Joan Baez, with whom Denver led an all-star version of "Blowin' in the Wind" and "Let the Sunshine In", joined by such diverse musical icons as Jennifer Warnes, Donna Summer, and Rick James.

In 1984, ABC Sports president Roone Arledge asked Denver to compose and sing the theme song for the 1984 Winter Olympics in Sarajevo. Denver worked as both a performer and a skiing commentator, as skiing was another of his enthusiasms. Denver composed "The Gold and Beyond", and sang it for the Olympic Games athletes, as well as local venues including many schools.[34]

In 1985, Denver asked to participate in the singing of "We Are the World" but was rejected, despite his obvious genuine commitment to charity work and his musical talent. According to Ken Kragen (who helped produce the song), Denver was snubbed because many people felt his image would hurt the credibility of the song as a pop-rock anthem. "I didn't agree with this assessment," Kragen said, but he reluctantly turned Denver down anyway.[37] Denver later wrote in his 1994 autobiography "Take Me Home" about the rejection, "It broke my heart not to be included."[38]

For Earth Day 1990, Denver was the on-camera narrator of a well-received environmental television program, In Partnership With Earth, with then-EPA Administrator William K. Reilly.

Due to his love of flying, Denver was attracted to NASA and became dedicated to America's work in outer space. He conscientiously worked to help bring into being the "Citizens in Space" program. In 1985, Denver received the NASA Exceptional Public Service Medal for "helping to increase awareness of space exploration by the peoples of the world", an award usually restricted to spaceflight engineers and designers. That same year, he passed NASA's rigorous physical exam and was in line for a space flight, a finalist for the first citizen's trip on the Space Shuttle in 1986. After the Space Shuttle Challenger disaster with teacher Christa McAuliffe aboard, Denver dedicated his song "Flying for Me" to all astronauts, and continued to support NASA.[34] He entered discussions with the Soviet space program about purchasing a flight aboard one of their rockets. The talks fell through after the price tag was rumored to be as high as $20 million.[39]

Denver testified before the Senate Labor and Commerce Committee on the topic of censorship during a Parents Music Resource Center hearing in 1985.[40] Contrary to his innocuous public image as a musician, Denver openly stood with more controversial witnesses like Dee Snider (of the heavy metal band Twisted Sister) and Frank Zappa in opposing the PMRC's objectives. For instance, Denver described how he was censored for "Rocky Mountain High", which was misconstrued as a drug song.[41]

Denver also toured Russia in 1985. His eleven concerts in the USSR were the first by any American artist in more than 10 years.[42] Denver returned two years later to perform at a benefit concert for the victims of the Chernobyl disaster.

In October 1992, Denver undertook a multiple-city tour of the People's Republic of China.[43] He also released a greatest-hits CD, Homegrown, to raise money for homeless charities. In 1994, he published his autobiography, Take Me Home, in which he candidly spoke of his cannabis, LSD, and cocaine use, marital infidelities, and history of domestic violence.[44] In 1996, he was inducted into the Songwriters Hall of Fame.

In 1997, Denver filmed an episode for the television series Nature, centering on the natural wonders that inspired many of his best-loved songs. His last song, "Yellowstone, Coming Home", composed while rafting along the Colorado River with his son and young daughter, is included.[45] In the summer of 1997, shortly before his death, Denver recorded a children's train album for Sony Pictures Kids Zone, All Aboard!, produced by longtime friend Roger Nichols.[46] The album consisted of old-fashioned swing, big band, folk, bluegrass, and gospel music woven into a theme of railroad songs. It won a posthumous Best Musical Album for Children Grammy, Denver's only Grammy.[47] His final concert was held in Corpus Christi, Texas, at the Selena Auditorium on October 5.

Personal life

[edit]Denver's first marriage, in 1967, was to Annie Martell of St. Peter, Minnesota.[48] She was the subject of his song "Annie's Song", which he composed in 10 minutes as he sat on a Colorado ski lift.[19][49] They lived in Edina, Minnesota, from 1968 to 1971.[50] After the success of "Rocky Mountain High", inspired by a camping trip with Annie and some friends, Denver bought a residence in Aspen, Colorado. He lived in Aspen until his death.[51] The Denvers adopted a boy, Zachary John, and a girl, Anna Kate, who, Denver said, were "meant to be" theirs.[34] Denver once said, "I'll tell you the best thing about me. I'm some guy's dad; I'm some little gal's dad. When I die, Zachary John and Anna Kate's father, boy, that's enough for me to be remembered by. That's more than enough."[52] Zachary was the subject of "A Baby Just Like You", a song that included the line "Merry Christmas, little Zachary" which he wrote for Frank Sinatra. Denver and Martell divorced in 1982. In a 1983 interview shown in the documentary John Denver: Country Boy (2013), Denver said that career demands drove them apart; Martell said they were too young and immature to deal with Denver's sudden success. To drive home the point that their assets were being split in the divorce, he cut their marital bed in half with a chainsaw.[53]

Denver married Australian actress Cassandra Delaney in 1988 after a two-year courtship. Settling at Denver's home in Aspen, the couple had a daughter, Jesse Belle. Denver and Delaney separated in 1991 and divorced in 1993.[19] Of his second marriage, Denver said that "before our short-lived marriage ended in divorce, she managed to make a fool of me from one end of the valley to the other".[44]

In 1993, Denver pleaded guilty to a drunken driving charge and was placed on probation.[53] In August 1994, while still on probation, he was again charged with misdemeanor driving under the influence after crashing his Porsche into a tree in Aspen.[53] Though a July 1997 trial resulted in a hung jury on the second DUI charge, prosecutors later decided to reopen the case, which was closed only after Denver's accidental death in October 1997.[53][54] In 1996, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) determined that Denver was medically disqualified from operating an aircraft due to his failure to abstain from alcohol; in October 1995, following Denver's drunk-driving conviction, the FAA had directed Denver to abstain from alcohol if he wished to continue flying airplanes.[55][56]

Beyond music, Denver's artistic interests included painting, but because of his limiting schedule, Denver pursued photography, saying once, "photography is a way to communicate a feeling." An exhibition of over 40 never-before-seen photographs taken by Denver debuted at the Leon Gallery in Denver, Colorado, in 2014.[57]

Denver was also an avid skier and golfer, but his principal interest was in flying. Denver's love of flying was second only to his love of music.[54] In 1974, Denver bought a Learjet to fly himself to concerts. He was a collector of vintage biplanes and owned a Christen Eagle aerobatic plane, two Cessna 210 Centurion airplanes, and a 1997 amateur-built Rutan Long-EZ.[34][56][54]

On April 21, 1989, Denver was in a plane accident while taxiing down the runway at Holbrook Municipal Airport in his vintage 1931 biplane. Denver had stopped to refuel on a flight from Carefree, Arizona, to Santa Fe, New Mexico. Reports stated wind gusts caught the plane, causing it to spin around and sustain extensive damage. Denver was not harmed in the incident.[58][59]

Death

[edit]

Denver died on the afternoon of October 12, 1997, when his light homebuilt aircraft, a Rutan Long-EZ with registration number N555JD, crashed into Monterey Bay near Pacific Grove, California, while making a series of touch-and-go landings at the nearby Monterey Peninsula Airport.[55] He was the plane's only occupant.[60][61] The official cause of death was multiple blunt force trauma resulting from the crash.

Denver was a pilot with over 2,700 hours of experience. He had pilot ratings for single-engine land and sea, multi-engine land, glider and instrument. Denver also held a type rating in his Learjet. He had recently purchased the Long-EZ aircraft, made by someone else from a kit,[62] and had taken a half-hour checkout flight with the aircraft the day before the crash.[63][64]

Denver was not legally permitted to fly at the time of the crash. In previous years, he had been arrested several times for drunk driving.[65] In 1996, nearly a year before the crash, the FAA learned that Denver had failed to maintain sobriety by not refraining entirely from alcohol and revoked his medical certification.[55][56] However, it was determined that the crash was not caused or influenced by alcohol use; an autopsy found no signs of alcohol or other drugs in Denver's body.[55]

The post-crash investigation by the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) showed that the leading cause of the crash was Denver's inability to switch fuel tanks during flight. The quantity of fuel had been depleted during the plane's flight to Monterey and in several brief practice takeoffs and landings Denver performed at the airport immediately before the final flight. His newly purchased amateur-built Rutan aircraft had an unusual fuel tank selector valve handle configuration. The handle had originally been intended by the plane's designer to be between the pilot's legs. The builder instead put it behind the pilot's left shoulder. The fuel gauge was also placed behind the pilot's seat and was not visible to the person at the controls.[55][56] An NTSB interview with the aircraft mechanic servicing Denver's plane revealed that he and Denver had discussed the inaccessibility of the cockpit fuel selector valve handle and its resistance to being turned.[55][56]

Before the flight, Denver and the mechanic had attempted to extend the reach of the handle using a pair of Vise-Grip pliers, but this did not solve the problem, and the pilot still could not reach the handle while strapped into his seat. NTSB officials' post-crash investigation showed that because of the fuel selector valve’s positioning, switching fuel tanks required the pilot to turn his body 90 degrees to reach the valve. This created a natural tendency to extend one's right foot against the right rudder pedal to support oneself while turning in the seat, which caused the aircraft to yaw (nose right) and pitch up.[55][56]

The mechanic said that he told Denver that the fuel sight gauges were visible only to the rear cockpit occupant. Denver had asked how much fuel was shown. He told Denver that there was "less than half in the right tank and less than a quarter in the left tank". He then provided Denver with an inspection mirror so he could look over his shoulder at the fuel gauges. The mirror was later recovered from the wreckage. Denver said that he would use the autopilot in flight to hold the airplane level while he turned the fuel selector valve. He turned down an offer to refuel the aircraft, saying that he would only be flying for about an hour.[55][56]

The NTSB interviewed 20 witnesses about Denver's last flight. Six of them had seen the plane crash into the bay near Point Pinos.[55][56] Four said the aircraft was originally heading west. Five said that they saw the plane in a steep bank, with four saying that the bank was to the right (north). Twelve described seeing the aircraft in a steep nose-down descent. Witnesses estimated the plane's altitude between 350 and 500 feet (110 and 150 m) when heading toward the shoreline. Eight said they heard a "pop" or "backfire" accompanied by a reduction in the engine noise level just before the plane crashed into the sea.

In addition to Denver's failing to refuel and his subsequent loss of control while attempting to switch fuel tanks, the NTSB determined other key factors that led to the crash. Foremost among these was his inadequate transition training on this type of aircraft and the builder's decision to put the fuel selector handle in a hard-to-reach place.[55][56] The board issued recommendations on the requirement and enforcement of mandatory training standards for pilots operating home-built aircraft. It also emphasized the importance of mandatory ease of access to all controls, including fuel selectors and fuel gauges, in all aircraft.

Legacy

[edit]

Upon the announcement of Denver's death, Colorado Governor Roy Romer ordered all state flags to be lowered to half-staff in his honor. Funeral services were held at Faith Presbyterian Church in Aurora, Colorado, on October 17, 1997, officiated by Pastor Les Felker, a retired Air Force chaplain, after which Denver's remains were cremated and his ashes scattered in the Rocky Mountains. Further tributes were made at the following Grammy and Country Music Association Awards.

In 1998, Denver posthumously received the Lifetime Achievement Award from the World Folk Music Association, which also established a new award in his honor.[66]

In 2000, CBS presented the television film Take Me Home: The John Denver Story loosely based on his memoirs, starring Chad Lowe as Denver. The New York Post wrote, "An overachiever like John Denver couldn't have been this boring".[67]

That same year on April 22, Hawk Mountain Sanctuary in Kempton, Pennsylvania dedicated a bench that was funded by donations as a tribute to his memory for that year's Earth Day. The bench sits on the South Lookout of the sanctuary.

On September 23, 2007, nearly 10 years after Denver's death, his brother Ron witnessed the dedication of a plaque placed near the crash site in Pacific Grove, California.

Copies of DVDs of Denver's many television appearances are now sought-after collectibles, especially his one-hour specials from the 1970s and his six-part series for Britain's BBC, The John Denver Show. An anthology musical featuring Denver's music, Back Home Again: A John Denver Holiday, premiered at the Rubicon Theatre Company in 2006.[68]

On March 12, 2007, the Colorado Senate passed a resolution to make Denver's trademark 1972 hit "Rocky Mountain High" one of the state's two official state songs, sharing duties with its predecessor, "Where the Columbines Grow".[69] The resolution passed 50–11 in the House, defeating an objection by Representative Debbie Stafford that the song reflected drug use, most specifically in the line "friends around the campfire and everybody's high". Senator Bob Hagedorn, who sponsored the proposal, defended the song as having nothing to do with drugs, but rather everything to do with sharing with friends the euphoria of experiencing the beauty of Colorado's mountain vistas. Senator Nancy Todd said, "John Denver to me is an icon of what Colorado is".[70]

On September 24, 2007, the California Friends of John Denver and The Windstar Foundation unveiled a bronze plaque near the spot where his plane went down. The site had been marked by a driftwood log carved by Jeffrey Pine with Denver's name, but fears that the memorial could be washed out to sea sparked the campaign for a more permanent memorial. Initially, the Pacific Grove Council denied permission for the memorial, fearing the place would attract ghoulish curiosity from extreme fans. Permission was finally granted in 1999, but the project was put on hold at the request of Denver's family. Eventually, over 100 friends and family attended the dedication of the plaque, which features a bas-relief of the singer's face and lines from his song "Windsong": "So welcome the wind and the wisdom she offers. Follow her summons when she calls again."[72]

To mark the 10th anniversary of Denver's death, his family released a set of previously unreleased recordings of his 1985 concert performances in the Soviet Union. This two-CD set, John Denver – Live in the USSR, was produced by Roger Nichols and released by AAO Music. These digital recordings were made during 11 concerts and then rediscovered in 2002. Included in this set is a previously unpublished rendition of "Annie's Song" in Russian. The collection was released November 6, 2007.[42]

On October 13, 2009, a DVD box set of previously unreleased concerts recorded throughout Denver's career was released by Eagle Rock Entertainment. Around the World Live is a 5-disc DVD set featuring three complete live performances with full band from Australia in 1977, Japan in 1981, and England in 1986. These are complemented by a solo acoustic performance from Japan in 1984 and performances at Farm Aid from 1985, 1987, and 1990. The final disc has two-hour-long documentaries made by Denver.

On April 21, 2011, Denver became the first inductee into the Colorado Music Hall of Fame. A benefit concert was held at Broomfield's 1stBank Center and hosted by Olivia Newton-John. Other performers participating in the event included the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band, Lee Ann Womack, and John Oates. Both his ex-wives attended, and the award was presented to his three children.

The John Denver Spirit sculpture is a 2002 bronze sculpture statue by artist Sue DiCicco that was financed by Denver's fans. It is at the Colorado Music Hall of Fame at Red Rocks Amphitheatre.

On March 7, 2014, the West Virginia Legislature approved a resolution to make "Take Me Home, Country Roads" the official state song of West Virginia. Governor Earl Ray Tomblin signed the resolution into law on March 8.[73] Denver is only the second person, along with Stephen Foster, to have written two state songs.

On October 24, 2014, Denver was awarded a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame in Los Angeles, California.[74]

Related artists

[edit]Denver began his recording career with The Mitchell Trio (the name "Chad" being legally dropped from the group's name upon the departure of its namesake founder); his distinctive voice can be heard where he sings solo on "Violets of Dawn", among other songs. He recorded three albums with the Trio, replacing Chad Mitchell as high tenor.[17] Denver also wrote a number of songs that were covered by the group, such as his hits "For Bobbi", "Leaving on a Jet Plane", as well as "Deal with The Ladies" (later recorded on his 1988 album, Higher Ground) and "Stay With Me". The group Denver, Boise, and Johnson, which had evolved from The Chad Mitchell Trio, released a single before he moved on to a solo career. The Trio also performed at college campuses across the United States.[18]

Bill Danoff and Taffy Nivert, billed as Fat City[75] and credited as co-writers of Denver's song "Take Me Home, Country Roads", were close friends of Denver and his family, appearing as singers and songwriters on many of Denver's albums until they formed the Starland Vocal Band in 1976. The band's albums were released on Denver's Windsong Records label, later known as Windstar Records.

Denver's solo recording contract resulted in part from the recording by Peter, Paul, and Mary of his song "Leaving on a Jet Plane", which became the sole number-one hit single for the group.[17] Denver recorded songs by Tom Paxton, Eric Andersen, John Prine, David Mallett, and many others in the folk scene. His record company, Windstar, is still an active record label today.[76] Country singer John Berry considers Denver the greatest influence on his own music and has recorded Denver's hit "Annie's Song" with the original arrangement.

Olivia Newton-John, an Australian singer whose across-the-board appeal to pop, middle-of-the-road, and country audiences in the mid-1970s was similar to Denver's, lent her distinctive backup vocals to Denver's 1975 single "Fly Away"; she performed the song with Denver on his 1975 Rocky Mountain Christmas special. She also covered his "Take Me Home, Country Roads", and had a hit in the United Kingdom (#15 in 1973) and Japan (#6 in a belated 1976 release) with it.[77] In 1976, Denver and Newton-John appeared as guest stars on The Carpenters' First Television Special, a one-hour special broadcast on the ABC television network.

Awards and recognition

[edit]- 1975 Favorite Pop/Rock Male Artist

- 1976 Favorite Country Album for Back Home Again

- 1976 Favorite Country Male Artist

- 1997 Best Musical Album For Children for All Aboard!

- 1998 Grammy Hall of Fame Award for "Take Me Home, Country Roads"

Other recognition

[edit]- Poet laureate of Colorado, 1977[34]

- People's Choice Awards, 1977[34]

- Ten Outstanding Young Americans, 1979[34]

- Freedoms Foundation Award, Valley Forge, Pennsylvania, 1980[78]

- Carl Sandburg's People's Poet Award, 1982[79]

- NASA Exceptional Public Service Medal, 1985[80]

- Albert Schweitzer Music Award, 1993[81]

Discography

[edit]Studio albums

- John Denver Sings (1966)

- Rhymes & Reasons (1969)

- Take Me to Tomorrow (1970)

- Whose Garden Was This (1970)

- Poems, Prayers & Promises (1971)

- Aerie (1971)

- Rocky Mountain High (1972)

- Farewell Andromeda (1973)

- Back Home Again (1974)

- Windsong (1975)

- Rocky Mountain Christmas (1975)

- Spirit (1976)

- I Want to Live (1977)

- John Denver (1979)

- Autograph (1980)

- Some Days Are Diamonds (1981)

- Seasons of the Heart (1982)

- It's About Time (1983)

- Dreamland Express (1985)

- One World (1986)

- Higher Ground (1988)

- Earth Songs (1990)

- The Flower That Shattered the Stone (1990)

- Different Directions (1991)

- Love Again (1996)

- All Aboard! (1997)

Filmography

[edit]Acting credits

- Owen Marshall, Counselor at Law: The Camerons Are A Special Clan (1973, as Clark)

- The Muppet Show as special guest

- McCloud: The Colorado Cattle Caper (1974, as Deputy Dewey Cobb)

- Oh, God! (1977, as Jerry Landers)

- Fire and Ice (1986, as Narrator)

- The Disney Sunday Movie: The Leftovers (1986, as Max Sinclair)

- The Christmas Gift (1986, as George Billings)

- Foxfire (1987, as Dillard Nations)

- Higher Ground (1988, as Jim Clayton)

- Walking Thunder (1997, as John McKay)

Alaska, the American Child

[edit]Alaska, the American Child is a documentary by John Denver. The filmed was funded heavily by John Denver but received some assistance from ABC.[82] The film was designed to gather support in Congress for H-39, which would have classified 95 million acres of federal-owned land in Alaska as parks and wildlife refuges.[82]

In the documentary, he travels through the State, showcasing its natural beauty, and the people who call Alaska home including Alaska Natives and bush pilots.[83] He starts the documentary off, and ends it, with the song American Child.[83] Two other songs of his are included in the documentary.[83]

Selected writings

[edit]- The Children and the Flowers (1979) ISBN 0-914676-28-8

- Alfie the Christmas Tree (1990) ISBN 0-945051-25-5

- Take Me Home: An Autobiography (1994) ISBN 0-517-59537-0

- Poems, Prayers and Promises: The Art and Soul of John Denver (2004) ISBN 1-57560-617-8

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Sterling, Christopher H.; O'Dell, Cary (April 12, 2010). The Concise Encyclopedia of American Radio. Routledge. ISBN 9781135176846 – via Google Books.

- ^ "The Music of John Denver". AllMusic.

- ^ Leigh, Spencer (October 14, 1997). "Obituary: John Denver". The Independent. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- ^ Maphis, Susan. "10 Best Selling Artists of the 1970s". mademan.com. Archived from the original on May 21, 2012. Retrieved May 16, 2012.

- ^ Ankeny, Jason. "John Denver Biography". AllMusic. Retrieved June 4, 2014.

- ^ "John Denver". Recording Industry Association of America.

- ^ "John Denver, A Rocky Mountain High Concert". The Florida Theatre. November 19, 2013. Archived from the original on June 19, 2018. Retrieved August 25, 2015.

- ^ Stunda, Hilary (October 7, 2011). "John Denver: An environmental legacy remembered". The Aspen Times. Retrieved January 30, 2023.

- ^ "Ancestry of John Denver compiled by William Addams Reitwiesner". Wargs.Com. Retrieved May 9, 2011.

- ^ "12 January 1961". This Day in Aviation. January 12, 2023. Retrieved October 12, 2023.

- ^ "John Denver's First Guitar displayed at the Musical Instrument Museum in Phoenix Arizona".

- ^ "John Denver". The Daily Telegraph. London. October 14, 1997. Archived from the original on July 6, 2010.

- ^ Pima County Recorders Office. Pima County Recorder's Website

- ^ a b John, Denver; Arthur, Tobier (October 11, 1994). Take Me Home: An Autobiography (Second ed.). Rocky Mountain Merchandise, LLC. ISBN 0517595370.

- ^ "Preservation Master Plan - Mansfeld Middle School, Tucson" (PDF).

- ^ "John Denver". 2002. Archived from the original on July 8, 2012. Retrieved May 9, 2011 – via Find Articles.

- ^ a b c d e f "Biography". johndenver.com. Retrieved August 17, 2010.

- ^ a b "The New Christy Minstrels". Thenewchristyminstrels.com. Archived from the original on August 5, 2020. Retrieved August 17, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g "John Denver Biography". Notablebiographies.com. Retrieved August 17, 2010.

- ^ La Ventana, vol. 37. Texas Tech University. 1962. hdl:2346/48702.

- ^ La Ventana, vol. 39. Texas Tech University. 1964. hdl:2346/48704.

- ^ Current Events Archived December 5, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Ruhlman, William (April 12, 1996). "Beginnings". Goldmine Magazine. Retrieved January 24, 2010.

- ^ "Denver, John". New Mexico Music Commission. Retrieved July 8, 2019.

- ^ "Top 100 Music Hits, Top 100 Music Charts, Top 100 Songs & The Hot 100". Billboard. September 12, 2008. Retrieved August 17, 2010.

- ^ "Artist Biography – John Denver". Countrypolitan.com. October 12, 1997. Archived from the original on February 21, 2001. Retrieved May 9, 2011.

- ^ John Denver: Rocky Mountain Wonderboy, James M. Martin, Pinnacle Books 1977

- ^ "1974–75 Emmy Awards". Infoplease.com. Retrieved August 17, 2010.

- ^ "Producer Jerry Weintraub reflects on his career". Reuters. November 1, 2011. Retrieved July 8, 2019.

- ^ Take Me Home: An Autobiography, John Denver and Arthur Tobier, Harmony Books, 1994.

- ^ "Charlie Rich Sets Fire to John Denver's CMA Slip 1975". youtube.com. December 27, 2019. Retrieved September 14, 2022.

- ^ "The Greatest : Features". Country Music Television. April 3, 1992. Archived from the original on March 20, 2012. Retrieved August 10, 2018.

- ^ thepiperchile. "ABBA on TV – Music for UNICEF – A Gift of Song Concert". Abbaontv.com. Archived from the original on July 7, 2011. Retrieved May 9, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Biography – The World Family of John Denver". June 28, 2006. Archived from the original on June 28, 2006. Retrieved July 9, 2019.

- ^ By (December 22, 1992). "Benefit planned to fight anti-gay law in colorado". Orlando Sentinel. Retrieved July 18, 2023.

- ^ a b Isenberg, Barbara (August 20, 1979). "Aspen Takes a Mellow Stance Towards John Denver's Gas Tank". The Record. Los Angeles Times News Service. Retrieved December 18, 2018.

- ^ Grayeb, Mike. "Behind the Song: "We Are the World"". HarryChapin.com. Retrieved May 9, 2011.

- ^ https://danmiller.typepad.com/dan_millers_notebook/2006/07/by_dan_miller_o.html [bare URL]

- ^ Mullane, R. (2006). Riding rockets: the outrageous tales of a space shuttle astronaut. New York: Scribner. ISBN 0-7432-7682-5. OCLC 62118471.

- ^ Deflem, Mathieu (2020). "Popular Culture and Social Control: The Moral Panic on Music Labeling". American Journal of Criminal Justice. 45(1):2–24: 2–24. doi:10.1007/s12103-019-09495-3. S2CID 198196942.

- ^ Denver, John. "John Denver: Senate Statement on Rock Lyrics & Record Labeling". American Rhetoric. Retrieved January 26, 2019.

- ^ a b "Windstar Foundation announcement". Wstar.Com. September 11, 2007. Archived from the original on June 15, 2011. Retrieved May 9, 2011.

- ^ "Biography – John Denver". johndenver.com. November 29, 2010. Retrieved December 10, 2022.

- ^ a b Denver, John, Take Me Home: An Autobiography, Crown Archetype Press, ISBN 978-0-517-59537-4 (1994)

- ^ "John Denver – Let this be a voice". Pbs.org Nature. Archived from the original on September 6, 2008. Retrieved May 9, 2011.

- ^ "Roger Nichols". The Daily Telegraph. London. June 16, 2011. Archived from the original on January 10, 2022.

- ^ "John Denver". Rock on the Net. Retrieved May 9, 2011.

- ^ Martin, Frank W. (February 26, 1979). "John Denver's Unsung Story". People. Retrieved August 15, 2018.

- ^ Pareles, Jon (October 14, 1997). "John Denver, 53, Who Sang of Natural Love and Love of Nature, Dies in a Plane Crash". The New York Times. section B. p. 11. Retrieved May 23, 2020.

- ^ John Denver in Minnesota Twin Cities Music Highlights

- ^ "John Denver". Midtod.com. October 5, 1997. Retrieved August 25, 2015.

- ^ Martin, Frank W. "John Denver's Unsung Story", People, February 26, 1979.

- ^ a b c d Story, Rob. "Dropping In: John Denver's Moral Victory". Ski Magazine. Archived from the original on July 12, 2012. Retrieved February 16, 2012.

- ^ a b c Castro, Peter (October 27, 1997). "Peaks & Valleys". People. Retrieved August 14, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Close-up: The John Denver Crash" Archived February 11, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, AVWeb. Retrieved February 16, 2012

- ^ a b c d e f g h i National Transportation Safety Board, "NTSB Public Meeting of January 26, 1999: Aircraft Accident involving John Denver in Flight Collision with Terrain/Water October 12, 1997, Pacific Ocean near Pacific Grove, CA, LAX-98-FA008", Washington, D.C., January 26, 1999

- ^ "Sweet, Sweet Life: The Photographic Works of John Denver". johndenver.com. December 18, 2013.

- ^ "Nation: John Denver Survives Air Crash". Los Angeles Times. April 21, 1989. Retrieved May 21, 2021.

- ^ "John Denver's Plane Crashes in California". The Washington Post. Retrieved July 20, 2021.

- ^ Kligman, David (October 13, 1997). "John Denver dies in crash // Singer's experimental plane falls into ocean". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on June 10, 2014. Retrieved July 17, 2019.

- ^ "Archive : Vault : Death Certificates: John Denver". Rockmine. Retrieved August 25, 2015.

- ^ "John Denver Plane Crash Inquiry Ends". Los Angeles Times. Associated Press. June 23, 1998.

- ^ "Denver's Long-EZ". Check-six.com. Retrieved August 25, 2015.

- ^ "NTSB Determines John Denver's Crash Caused by Poor Placement of Fuel Selector Handle Diverting His Attention During Flight" (Press release). National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB). Archived from the original on July 24, 2012. Retrieved December 7, 2009.

- ^ Coile, Zachary; Gurnon, Emily; Hatfield, Larry D. (October 13, 1997). "John Denver dies in crash". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved September 26, 2016.

- ^ Noble, Richard E. (2009). Number #1 : the story of the original Highwaymen. Denver: Outskirts Press. pp. 265–267. ISBN 9781432738099. OCLC 426388468.

- ^ Buckman, Adam. "Home Movie Disses Denver", New York Post, April 29, 2000.

- ^ "John Denver and Friends Rocky Mountain High". Shellworld.net. April 17, 2009. Retrieved May 9, 2011.

- ^ "Colorado State Song Rocky Mountain High composed by John Denver". Netstate.com. Retrieved August 25, 2015.

- ^ Denver Post, March 13, 2007

- ^ "John Denver Sanctuary, Aspen, Colorado". Aspenportrait.com. October 12, 1997. Retrieved May 9, 2011.

- ^ "John Denver Memorial Plaque Pacific Grove". Johndenverclub.org. Retrieved May 9, 2011.

- ^ ""Country Roads" To Become Fourth Official West Virginia State Song". Eyewitness News. Archived from the original on March 8, 2014. Retrieved July 9, 2019.

- ^ Baskin, Gregory (October 16, 2014). "John Denver To Get Posthumous Star on Hollywood Walk of Fame [Video]". Guardian Liberty Voice. Retrieved October 18, 2014.

- ^ Flippo, Chet (May 8, 1975). "John Denver: His Rocky Mountain Highness". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on February 6, 2018. Retrieved February 6, 2018.

- ^ John Denver, The Windstar Greatest Hits, retrieved July 8, 2018; the record was published in December 2017, suggesting the label is still active, but it appears to be mostly reissuing John Denver's music

- ^ "Take Me Home, Country Roads – John Denver". Last.fm. Retrieved July 8, 2019.

- ^ Along with U.S. Senator Jake Garn, U.S. Ambassador Shirley Temple Black, actor James Stewart, and Tom Abraham, a businessman from Canadian, Texas, who worked with immigrants seeking to become U.S. citizens. Cited in "Tom Abraham to be honored by Freedoms Foundation Feb. 22", Canadian Record, February 14, 1980, p. 19

- ^ "Awards". johndenver.com. December 10, 2010. Retrieved July 8, 2019.

- ^ Kroll, David (December 31, 2010). "John Denver, friend of science, born today in 1943 | Take As Directed". Take As Directed. PLOS. Archived from the original on June 17, 2018. Retrieved June 17, 2018.

- ^ "WHEN IT WAS OVER, OVER THERE". The Washington Post. May 28, 1995. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved April 29, 2019.

- ^ a b Collins, Nancy (May 11, 1978). "'Alaska, the American Child'". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved June 7, 2023.

- ^ a b c John Denver in Alaska / The American Child [09/03/1978] (Full) Rare!!, October 23, 2016, retrieved June 7, 2023

Notes

[edit]- ^ One biological child and two adopted children.

Sources

[edit]- Flippo, Chet (1998) "John Denver", The Encyclopedia of Country Music, Paul Kingsbury, editor, New York: Oxford University Press. p. 143.

- Martin, James M. (1977) John Denver: Rocky Mountain Wonderboy, Pinnacle Books. (out of print) Biography of Denver with insight into Denver's impact of the 1970s music industry.

- Orth, Maureen, "Voice of America", Newsweek, December 1976. Includes information on the role of Weintraub in shaping Denver's career, which has since been edited out of later versions of his biography.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- John Denver at IMDb

- John Denver discography at Discogs

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- John Denver's childhood home in Tucson Arizona website Archived April 22, 2024, at the Wayback Machine

- John Denver

- 1943 births

- 1997 deaths

- 20th-century American guitarists

- 20th-century American male actors

- 20th-century American male singers

- 20th-century American male writers

- 20th-century American poets

- 20th-century American singer-songwriters

- Accidental deaths in California

- American acoustic guitarists

- American autobiographers

- American ballad musicians

- American country guitarists

- American country singer-songwriters

- American environmentalists

- American folk guitarists

- American folk singers

- American folk-pop singers

- American glider pilots

- American male film actors

- American male guitarists

- American male singer-songwriters

- American male television actors

- American people of German descent

- Aviators killed in aviation accidents or incidents in the United States

- Colorado culture

- Colorado Democrats

- Country musicians from Colorado

- Grammy Award winners

- Guitarists from New Mexico

- Mercury Records artists

- Musicians killed in aviation accidents or incidents

- New Mexico Democrats

- People from Aspen, Colorado

- People from Roswell, New Mexico

- People named in the Paradise Papers

- Poets Laureate of Colorado

- RCA Records artists

- Singer-songwriters from Colorado

- Singers from Denver

- Singers from New Mexico

- Songwriters from New Mexico

- Texas Tech University alumni

- Victims of aviation accidents or incidents in 1997